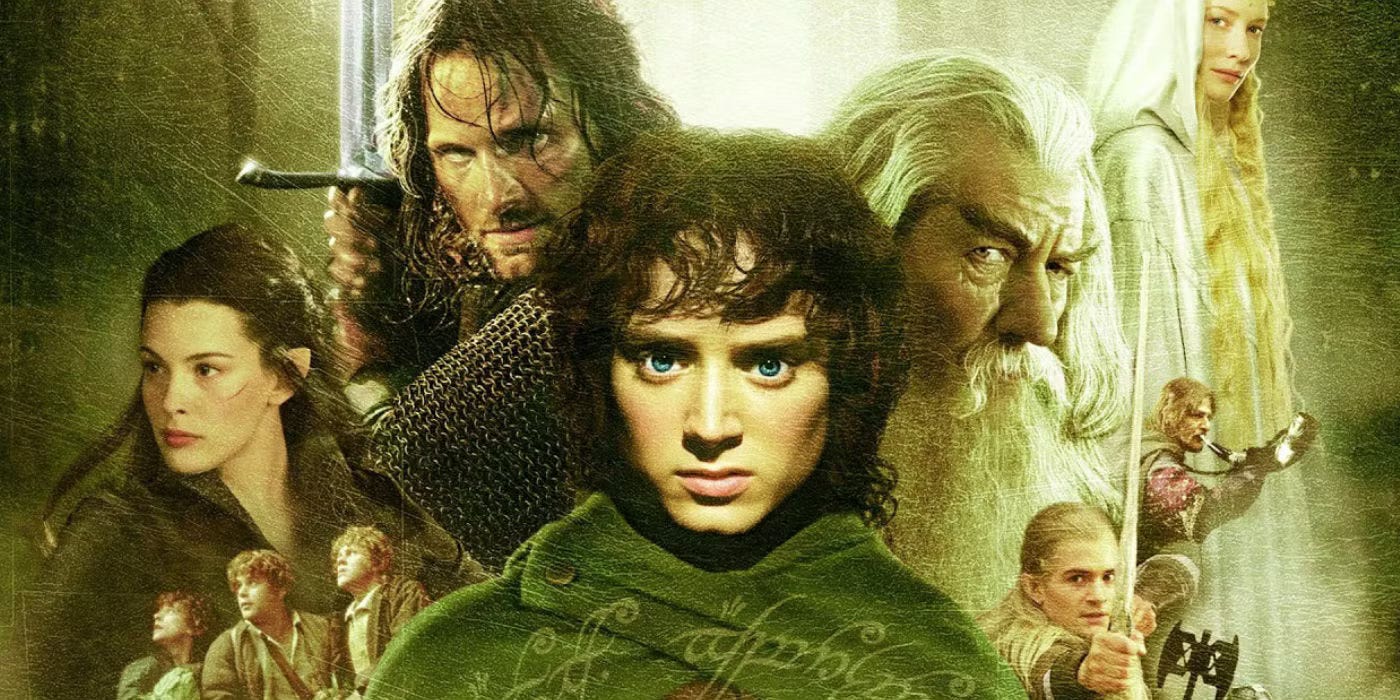

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001)

This is the most daunting review that I’ve ever had to write. The Lord of the Rings is far more than a movie trilogy. It’s the glue that’s kept my family together, it’s a landmark of my childhood, it’s a shared language and it’s a common reference point that’s allowed me to find comfort and friendship wherever I go. In adapting J. R. R. Tolkien’s mammoth trilogy to the screen, Peter Jackson achieved the impossible. He made three high fantasy blockbusters that bewitched everyone who saw them. When filming of the trilogy began in 1999, movies about elves, orcs and wizards weren’t supposed to dominate the box office and clean up at the most prestigious awards ceremonies on the planet. Jackson changed the rule book and he created a sensation that swept the Earth. Everyone from Russia to Rio had heard of Frodo Baggins, and every slightly annoying man on Earth was performing a Gollum impression at the dinner table. The Lord of the Rings wasn’t just a financial and critical smash, it inspired a passion unlike anything before or since.

For those unfamiliar with the series, The Lord of the Rings is the story of an epic quest. A group comprised of an allied collection of creeds and races set out to destroy a magical ring. It was forged by the dark lord Sauron in the fires of a volcano named Mount Doom, and it can only be destroyed in the lava flows that gave it life. The ring is sentient, always trying to tear the group apart and play on the worst instincts of its bearer. The fellowship’s quest takes them across the realms of Middle Earth, through treacherous mines, war-torn plains, ancient forests and labyrinths of razor-sharp rocks. There’s death, betrayal, tragedy, resurrection, defeat and victory. Eternal friendships are forged, all manner of strange creatures are encountered, and the world of Middle Earth goes to war. Amidst the high politics of the warring kingdoms and the grand powers of the mighty elves and ancient wizards, the hobbits are the underdogs, small folk from a peaceful land who are often underestimated. The ring is carried by a hobbit named Frodo Baggins (Elijah Wood).

The Fellowship of the Ring is the first entry in The Lord of the Rings trilogy, and it’s a glorious work of effortless worldbuilding, adventure and English romanticism. Before the quest to destroy the one ring begins, Jackson takes his time establishing the Shire and the ways of the hobbits. This is necessary background work, cementing the politics and culture of Middle Earth, but it’s delivered with touching emotion and genuine passion for the restfulness and serenity of rural life. For me, the Shire will always be Shropshire, the county where I grew up. Howard Shore’s beautiful score, cinematographer Andrew Lesnie’s brilliantly verdant images and the well-cast crotchety, pipe-smoking hobbits paint a vivid picture of rosy, cosy life in England’s shires. I prefer it to the real thing. Jackson understands that the fetishisation of the English countryside is at the heart of Tolkien’s story, that the author’s love for the green shires and scepticism for industrialisation fuels the grand narrative of the trilogy. To cherish the quest, you have to understand exactly where Frodo Baggins and his loyal companion Samwise Gamgee (Sean Astin) come from.

Jackson and his co-writer (and wife) Fran Walsh stick true to the texture of Tolkien’s worldview. The scholarly author writes in the tradition of William Blake, taking a romantic conservative view of English society. The cauldrons and furnaces of Mordor and Isengard echo the “dark satanic mills” that Blake so despised, while the structure of the hobbit world is perfectly in keeping with the conservative view of a slow-growing organic society. There’s no organised class politics or ideological strife in the shire, just a community of little people who know their place and allow Middle Earth’s aristocrats to rule in their own interests. The few women of the shire stay at home, West Country-accented hobbits do the gardening and the RP-accented homeowners seem to have a more pronounced voice over hobbit affairs. This is an idealised view of England before war, before socialism, rationing and Clement Attlee’s redistribution of wealth.

This first film moves from the well-kept homes and smoky pubs of the shire into the realms of men and elves, taller creatures with a history of warfare and wizardry. The hobbits have no magic and no desire to take arms or fight for grand ideals. They are content to stay home, eat, drink and be merry. Frodo and his uncle Bilbo (Ian Holm) buck the trend, yearning for adventure and exploration. Chuckling hobbitophile wizard Gandalf tasks Frodo with the quest of transporting Bilbo’s old ring to Rivendell, a beautiful and ancient elven city. Frodo eventually becomes the centre of the fellowship of free creatures, the unlikely bearer of the most powerful weapon in Middle Earth. The ring is Sauron’s, and it wants to corrupt Frodo’s heart. Jackson allows us to fully appreciate Frodo’s courage by spending so much time establishing the shire and the ways of the hobbits. Frodo is an original and he’s making history. He may be the first hobbit to take arms alongside men and elves. His innocence provides him with strength against the ring’s powers.

The second and third entries in the trilogy have gigantic battles, delicate politics and complex narratives that fracture into three or four connected storylines, with each splinter group of the fellowship pursuing their own goals. Here, for the only time, the nine are united and marching to Mordor together. Walsh, Jackson and Boyens’ script focuses on the differences between each member of the group. Emotionless elf Legolas (Orlando Bloom) is fiercely skilled but cold and direct. Passionate dwarf Gimli (John Rhys-Davies) is rash and hot-headed. Headstrong Boromir is empathetic but easily tempted. Noble ranger Aragorn (Viggo Mortensen) is perfect in every way. Cheeky hobbits Merry and Pippin provide comic relief. The film follows the group as it splinters. Members die, and in the first grand battle the fellowship is ended. Frodo is always at the centre. From the moment that he becomes the ring bearer, he knows what he must do, even if it means leaving his allies behind. Wars and diplomacy are for men, secret missions of great courage and resilience are fulfilled by the plucky hobbits.

In recent appraisals of the trilogy, the same point is made again and again: compared to today’s Disney-Marvel green screen blockbusters, The Lord of the Rings is infinitely more tactile and authentic. Jackson’s decision to shoot on location using the mountains, forests and fields of his native New Zealand is one of the trilogy’s many masterstrokes. CGI is only used when absolutely necessary, and it looks significantly better than the (supposedly) more advanced technology used today. Tricks of forced perspective are used to make the hobbits actors look smaller and fantastically detailed practical models conjure up the towers of Isengard and Mordor, territories claimed by the dark powers of allied wizards Sauron and Saruman (Christopher Lee). As a feat of production design, The Lord of the Rings is dazzling and inspirational. Jackson’s faith in practical effects pays off in a fantasy world that never feels artificial, cheap or flimsy.

Jackson’s direction is awe-inspiring. He sets the scene with David Lean-style panoramas of breath-taking landscapes before swooping his camera across vast chasms and orc armies, following the flow of battle and the passage of elven arrows with supernatural ease. Prior to his Tolkien adaptations, Jackson was best known for gory creature features like Bad Taste and Braindead, but he had also helmed a superb drama: Heavenly Creatures. Lord of the Rings sees Jackson combine his strengths, relishing the gooey, slimy textures of the brilliantly detailed orcs before transitioning to silky-smooth sequences of ethereal splendour in Rivendell. Jackson’s camera is always in the right place, always perfectly positioned to capture the superb production work, capture the thrill of battle and highlight the beauty of his cast. Scenes between loves Aragorn and Arwen (Liv Tyler) are breathlessly intimate. Scenes in the birthing pits of Isengard are really quite gross.

The Fellowship of the Ring shows the path that most blockbusters since have refused to take. Its greatest strengths are its practical approach and its sincerity. Merry and Pippin’s enjoyably goofy shenanigans aside, Fellowship presents its high fantasy concepts without undercutting them. Audiences are expected to watch high councils of elves and portentous declarations on the deep history of Middle Earth without snarky quips, pop culture references or pithy one-liners. There’s no Joss Whedon ‘wit’ or self-aware, tacky post-modern comedy. Thank god. The Avengers took a very different path and the world is worse for it. Look to the hobbits, look to Jackson’s fidelity to Tolkien’s grand vision and look to fantasy with heart and ambition. Jackson could have reduced The Lord of the Rings into a basic series of sword and sorcery adventure movies, but he refused to so. With intelligent casting and a commitment to the brains and feeling of the novels, he created great art that was accessible and rich. Fellowship begins the trilogy in style, with warmth, elegance and sumptuous detail. This is the film where the hobbits leave home. Things only get grander from here…